Award of Excellence: Fuel of the Future, Now

This premier category recognizes a photographer’s long-term story, project, or essay that explores issues related to the environment, natural history, or science. This could include a facet of human impact on the natural world, scientific discovery, coverage of plant or animal habitat, climate concerns, or similar topics.

Fuel of the Future, Now

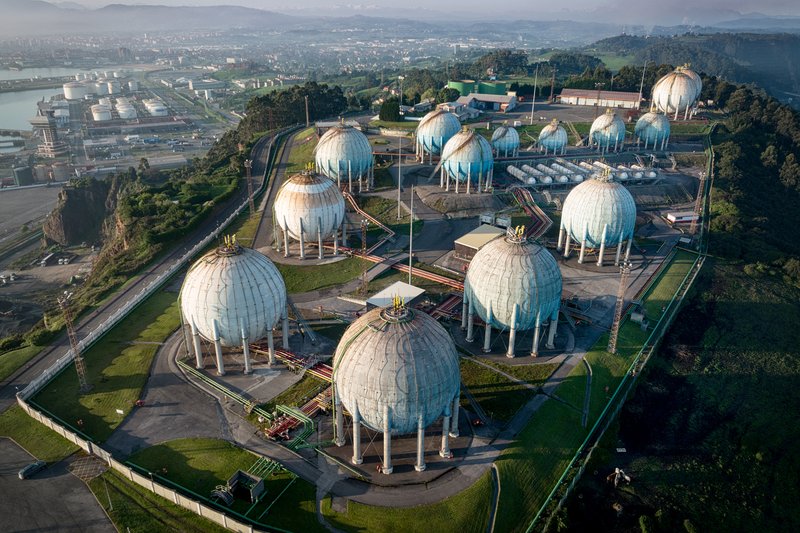

The fuel of the future is here, and energy pioneers are hard at work bringing in the dawn of a new era. Hydrogen is the world’s most abundant element. It makes up the sun and has the potential to power economies, leaving only water as waste. Though long discounted as too expensive to produce, the spike in geopolitical risks associated with Russian gas and governmental pledges to meet net-zero goals are jump-starting a global race to dominate hydrogen production. I started to document the story of energy in Russian during the 2010s, at that time focusing on gas and oil. It was already clear Putin was using Gazprom’s vast fossil resources to control Europe, which depends on its cheap supply of natural gas. Today these countries are being blackmailed by Kremlin’s weaponisation of energy supply. Green hydrogen, or hydrogen made sustainably, became my focus in 2022 after the European Commission named it as its leading candidate to replace fossil fuels. I want to see if the universe’s oldest element can really spark an energy revolution. And I want to see if it really can help Europe wean off Russian gas and meet its net-zero goal at the same time. I traveled to the Netherlands, Europe’s most advanced hydrogen valley shows what an integrated hydrogen society looks like, with buses that leaves only water as waste to schools teaching about hydrogen and a futuristic fuelling station on a highway. I moved further north to the crisp cold of the Arctic to see how so-called green hydrogen is already underway to decarbonise our most pollutive industry. I met innovators at a Swedish company that produced the world’s first batch of fossil-free “Green Steel”, which is revolutionising the entire metals industry, potentially reducing world CO2 emissions by 10 percent or more. In Croatia, an inventor made a machine that ingests wastes such as human faeces and produces hydrogen-rich gas, at once solving the problem of waste management and clean-energy production. Finally, I ventured to the Sahara Desert. With its vast space and sunshine, the arid region has become a hotspot for energy transition. Covering just two percent of the desert with solar panels could generate enough energy to replace Europe’s import of Russian gas. This time though, Africa stands to benefit. One example: the iron ore mining company that run the world’s longest train to transport its ore will one day make its own hydrogen to create fossil-free steel, just like the Swedes.

Fuel of the Future, Now

The fuel of the future is here, and energy pioneers are hard at work bringing in the dawn of a new era. Hydrogen is the world’s most abundant element. It makes up the sun and has the potential to power economies, leaving only water as waste. Though long discounted as too expensive to produce, the spike in geopolitical risks associated with Russian gas and governmental pledges to meet net-zero goals are jump-starting a global race to dominate hydrogen production. I started to document the story of energy in Russian during the 2010s, at that time focusing on gas and oil. It was already clear Putin was using Gazprom’s vast fossil resources to control Europe, which depends on its cheap supply of natural gas. Today these countries are being blackmailed by Kremlin’s weaponisation of energy supply. Green hydrogen, or hydrogen made sustainably, became my focus in 2022 after the European Commission named it as its leading candidate to replace fossil fuels. I want to see if the universe’s oldest element can really spark an energy revolution. And I want to see if it really can help Europe wean off Russian gas and meet its net-zero goal at the same time. I traveled to the Netherlands, Europe’s most advanced hydrogen valley shows what an integrated hydrogen society looks like, with buses that leaves only water as waste to schools teaching about hydrogen and a futuristic fuelling station on a highway. I moved further north to the crisp cold of the Arctic to see how so-called green hydrogen is already underway to decarbonise our most pollutive industry. I met innovators at a Swedish company that produced the world’s first batch of fossil-free “Green Steel”, which is revolutionising the entire metals industry, potentially reducing world CO2 emissions by 10 percent or more. In Croatia, an inventor made a machine that ingests wastes such as human faeces and produces hydrogen-rich gas, at once solving the problem of waste management and clean-energy production. Finally, I ventured to the Sahara Desert. With its vast space and sunshine, the arid region has become a hotspot for energy transition. Covering just two percent of the desert with solar panels could generate enough energy to replace Europe’s import of Russian gas. This time though, Africa stands to benefit. One example: the iron ore mining company that run the world’s longest train to transport its ore will one day make its own hydrogen to create fossil-free steel, just like the Swedes.